Griffin Wagner is a 4th-year Biology major studying guinea worm disease prevention in sub-Saharan Africa with Dr. Jeannette Yen.

How long have you been an undergraduate researcher at Georgia Tech?

I’ve been working with Dr. Yen for the past four years, joining in my first month on campus at Georgia Tech

How did you get involved with undergraduate research?

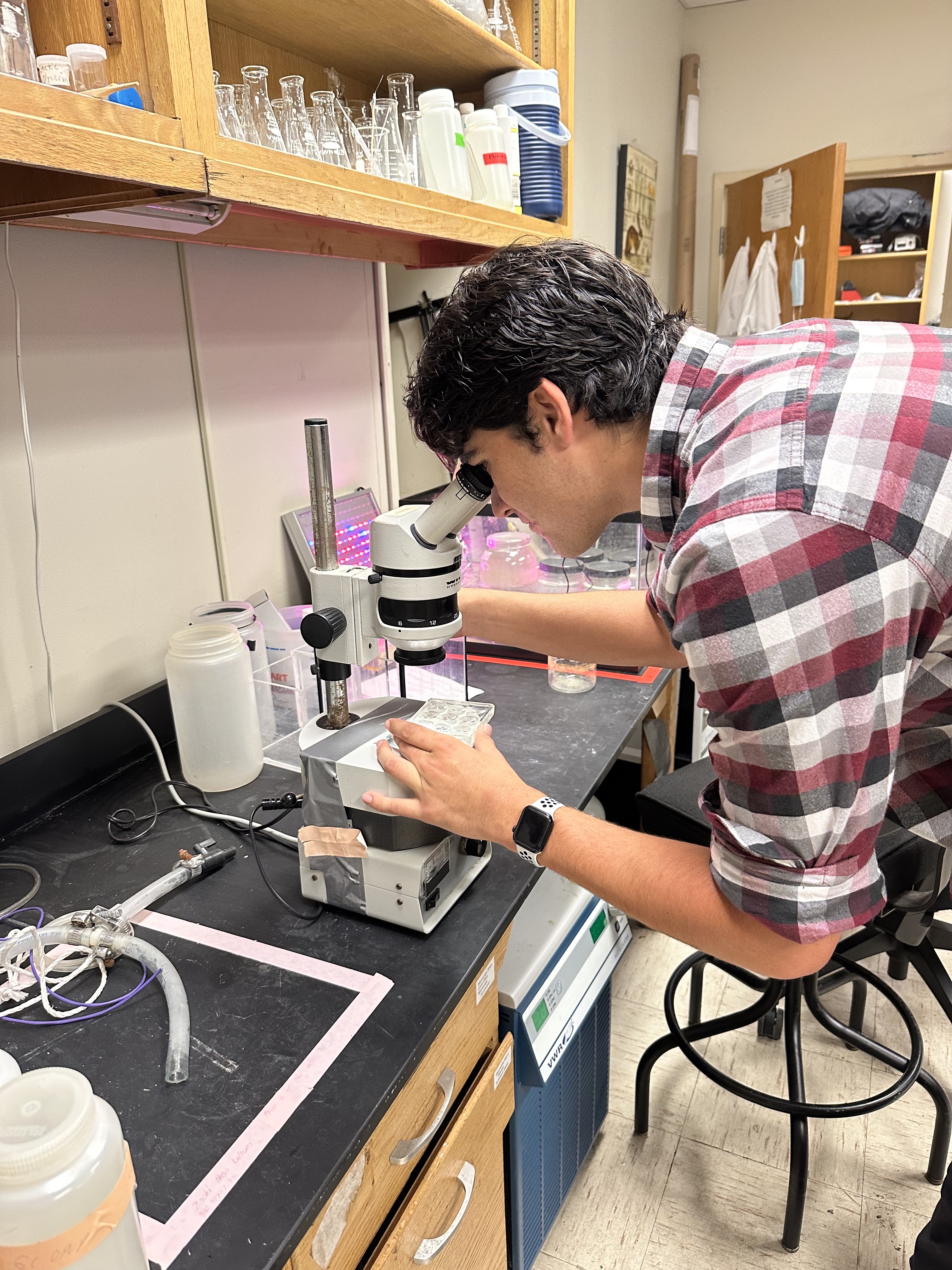

My first semester at Georgia Tech was plagued by online classes and virtual labs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Desiring a wet lab experience, I reached out to several professors at Georgia Tech and Dr. Yen welcomed me to learn about her work. I started on a project studying carbon flux and plankton dynamics in Shoshone National Forest where I got to travel to Montana and Wyoming. In my second semester, our lab received a grant from the Jimmy Carter Center to study guinea worm disease and I began to lead several projects. It was incredibly exciting to learn about copepod and plankton research and I’ve loved it ever since.

What are you working on?

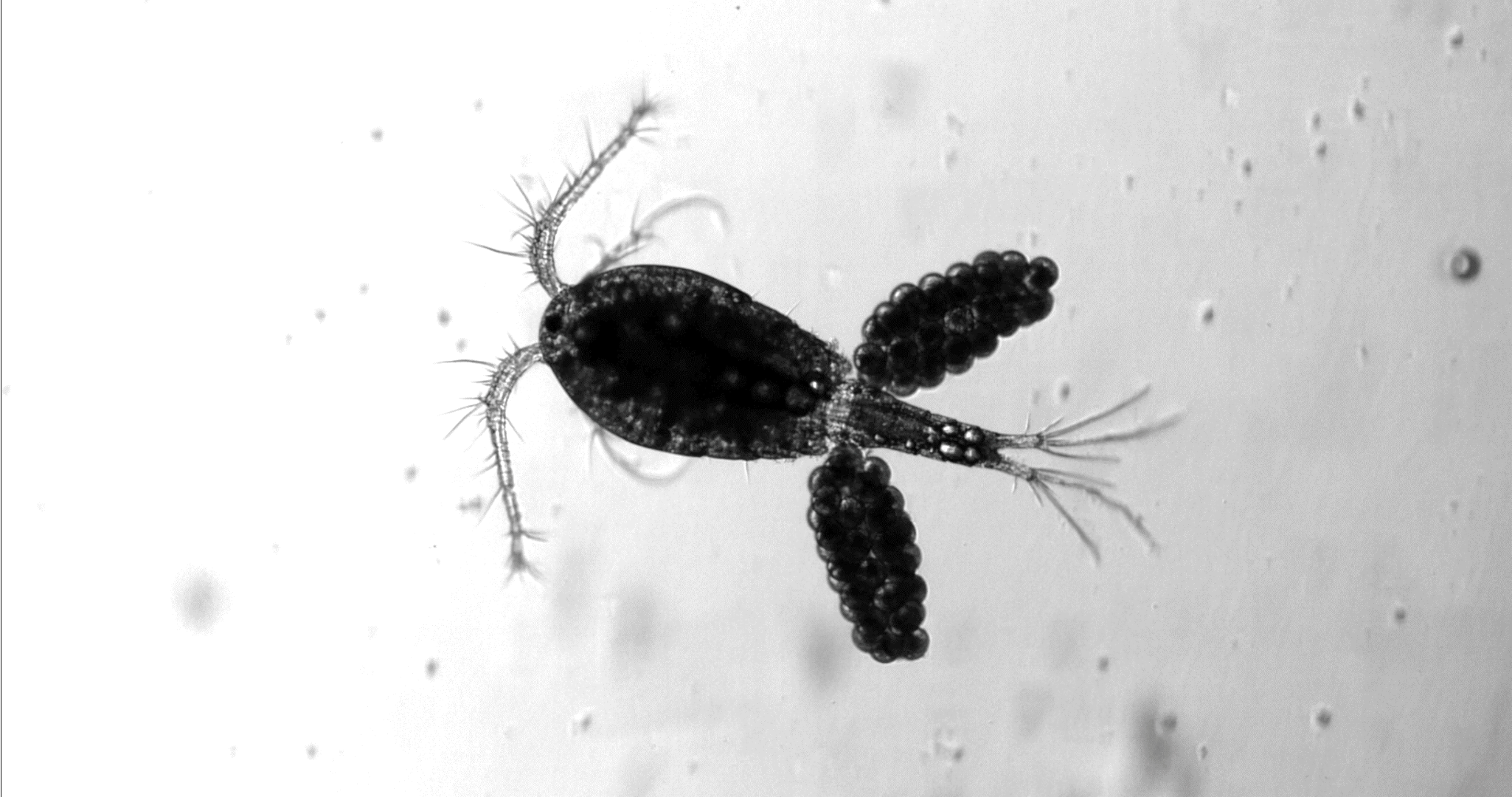

Through Dr. Yen’s lab, I have work on several projects that all focus on copepods. Copepods, ranging from 0.5mm to 8mm, are group of invertebrate crustaceans (or plankton) existing in almost every body of water across the planet. Copepods are incredibly important for all the ecosystems they inhabit serving a crucial link in the food chain in most environments.

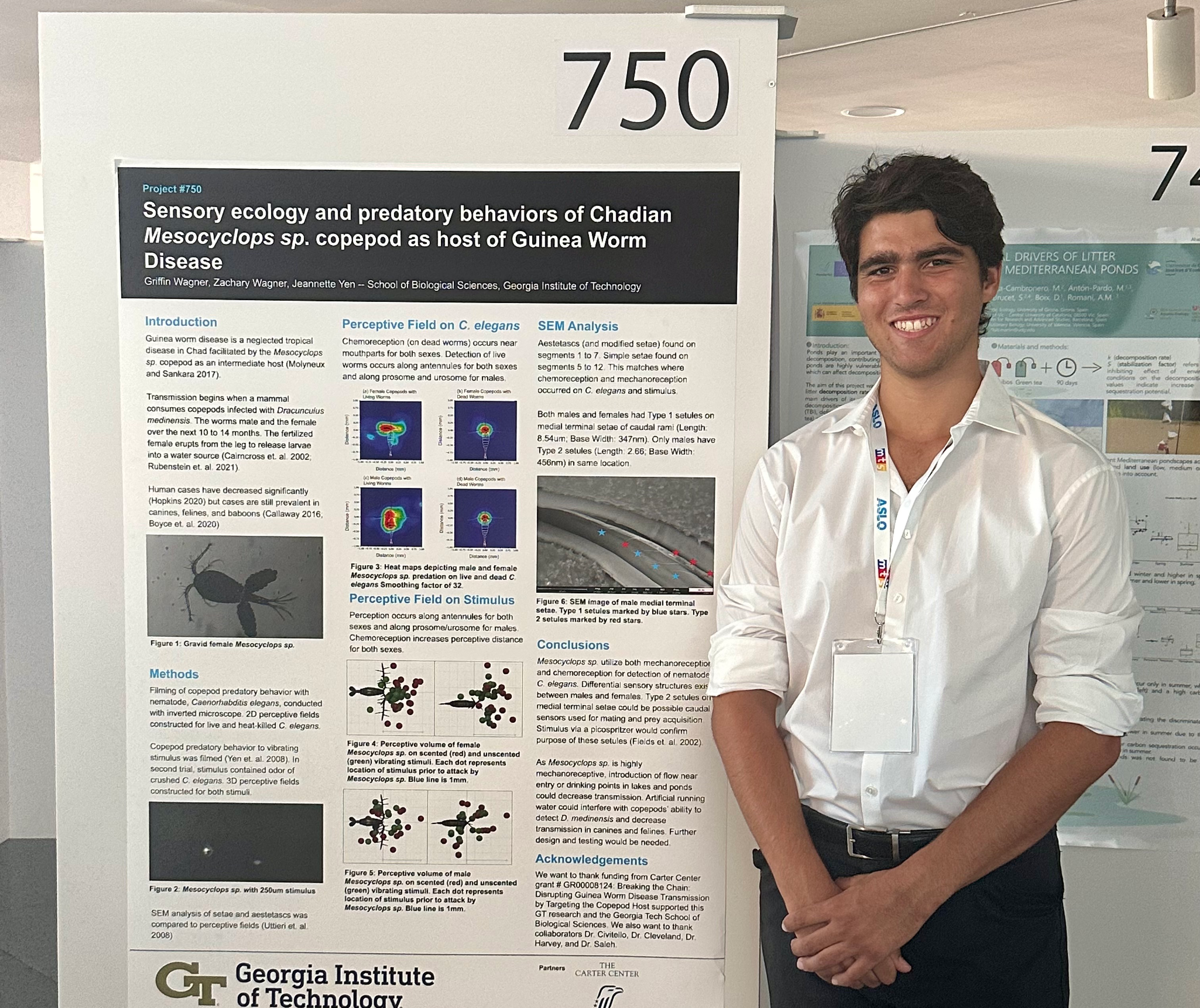

My main project is the study of guinea worm disease prevention in sub-Saharan Africa with support from the Carter Center. Guinea worm infections have fallen from 3.6 million humans per year in 1986 to just 15 in 2021 due to impressive work from the Carter Center; however, cases in canines, felines, and baboons are still prevalent. Guinea worm disease occurs when a copepod consumes the guinea worm; then, a mammal drinks water with the infected copepods. The worm grows from 1mm inside the mammal’s intestine to 1m and emerges from the mammal’s leg, immobilizing the host for up to a month. My work has focused on understanding how the copepod preys upon the worm. Our goal is to characterize the mechanisms by which the copepod can perceive and consume the worm. These results guide the design of non-chemical strategies to prevent capture of the worm in lakes and ponds in sub-Saharan Africa to prevent guinea worm disease transmission.

Additionally, I work as the only undergraduate researcher on an interdisciplinary project with researchers from Bigelow labs and Oklahoma State University on the variation of plankton body size and swimming kinematics in response to temperature and viscosity. Three congeners of the Euchaeta copepods are studied in Maine, Hawaii, and Antarctica to understand how viscosity and temperature affect plankton evolution.

What is your favorite thing about research/researching?

Field work has always been incredibly exciting to me. For my work on understanding viscosity’s role in plankton evolution, I’ve travelled with my lab to Friday Harbor Labs in Washington and Natural Energy Labs in Hawaii to work with copepods in their natural environment. It has been incredibly rewarding to work in the field and see parts of the world I’ve never had the chance to experience.

What are your future plans and how has research influenced them?

Before working with the Carter Center on guinea worm disease, I’d never heard of the field of disease ecology. This field focuses on understanding how diseases spread through an ecosystem and designing mechanisms to disrupt disease transmission at every link. I’ve always known I wanted to pursue graduate-level study in biology, but this work has narrowed my focus to aquatic disease ecology. I’ve become incredibly interested in this field and I now plan to pursue a Ph.D. in disease ecology because of the work with Dr. Yen and the Carter Center.